Earth's Orbit Lesson

Overview

One of the first questions students often ask when they learn that the force of gravity exists not just on objects on the Earth, but between the Earth and the Sun, is "why doesn't the Earth fall into the Sun?" The orbit of the Earth is a balance between the Earth's momentum and the gravitational pull between the Earth and the Sun.Preparation and Materials

The teacher should be familiar with the GalaxSee application (for those unfamiliar with this software, there is an online tutorial), have it loaded on a computer, and have some means of displaying the monitor to the class.Objectives

Students will- use a computational model to explore how the orbit of the Earth might change if its velocity were different. They will see how a slight change in a circular orbit will produce an elliptical orbit.

- practice accurately observing and recording data from a scientific experiment.

- communicate and defend a scientific argument while collaborating with other students.

Standards

This lesson fulfills portions of the following standards and curriculum guidelines:- NSES content standard

(9-12 A) on

science as inquiry, including:

- Use technology and mathematics to improve investigations and communications.

- Communicate and defend a scientific argument.

- Use technology and mathematics to improve investigations and communications.

- NSES content standard (9-12 D) on origin and evolution of the universe.

- NSES content standard (9-12 E) on understandings about science and technology.

- DoDDs Science 9 objectives, including:

- Use of computational models.

- Use careful systematic observation and data collection to obtain

valid information.

- Relate force, motion, energy and power.

- Use of computational models.

Activities

- Prior to this activity, the students should have learned the features of the solar system and that the Earth revolves around the Sun once per year.

- Make the following points about planetary orbits:

- The further a planet is from the Sun, the longer it takes to get

around the Sun, and the lower the speed at which it travels.

- None of the planets travel in a perfect circle around the Sun,

but the Earth travels in an almost perfect circle.

- The pull of the Earth on the Sun is just as large as the pull

of the Sun on the Earth, the Sun is just so massive that the same force does

no produce as much of a change in motion. (The same is true of the pull between

the student and the Earth, the student is pulling just as hard on the Earth

as the Earth is on the student.)

- If we are to accomplish anything in science, it is extremely important

that we are careful observers.

- The further a planet is from the Sun, the longer it takes to get

around the Sun, and the lower the speed at which it travels.

- With the monitor displayed so that the students can see it, open the "Galaxy Setup" from the Galaxy menu and choose 2 stars. The distribution should be either spherical or disc. The other fields will be changed later, and the value is unimportant. Hit OK to create a new galaxy. You also want to set the scale to the solar system by selecting "Scale" under the Galaxy menu and selecting Solar System. You may want to Zoom in and this can be done under the View menu. Then open the list by selecting "Show List" from the Galaxy menu.

- Set the initial position, velocity, mass, and color of the sun by double clicking on the each of the values for the first object in the star list, changing the values and then hitting Enter.

- Consider having the students look up the mass of the Sun in Earth masses. (330000) They should input a mass for the sun in these terms of Earth masses.

- Show a picture of the orbit of the Earth from a top down view, with the Sun at the origin. Ask the students what the coordinates of the Sun's position are. The coordinates of the Sun's velocity? (All should be zero)

- Define for the students the Astronomical Unit (AU) and ask them how many AUs the Earth is from the Sun. (1)

- Using a diagram of the Earth's orbit, show the Earth 1 AU from the origin on the x-axis. Ask the students to determine the coordinates of the Earth. (1,0,0)

- (Note: The y-axis points up, the z-axis points out of the screen, and the x-axis points to the right.)

- Do not ask the students what the velocity of the Earth should be, but ask them in what direction the Earth would be moving at the point at which it was on the positive x-axis in the diagram.

- Put in an initial guess of 1 AU/day for the velocity in the y direction and make both the x and z velocities equal zero. When you finish changing all values, hit OK.

- Save the model (by a name you will remember and in a location you will remember) before you run the simulation. (This will save you a lot of time recreating the input, trust me!!)

- Have the students watch carefully as you run the model by selecting "Run Simulation" from the Galaxy menu. (The planet shoots off quickly, the velocity is too large.)

- Have the students run the model repeatedly, with different (appropriate) values of the initial velocity. What velocity will make the Earth travel in a perfect circle? (The answer you should eventually arrive at is 2*pi/365 or approximately 0.01721.) (At 0.02, the path of the earth is still clearly very elliptical and at 0.01, the earth almost falls into the sun, so you could guess that the velocity must be between these two and keep testing.)

- Note: This is a numerical solution, and can accumulate numerical error. For objects that make a close approach to the Sun, sometimes inaccuracies can make the object appear to move into a small circular orbit around the Sun. If the students find this happening, have them run the same model with a smaller time step and compare the results. For more information about detecting and controlling error, see the section about the info window in the GalaxSee tutorial on the Shodor Education Foundation web site.

Discussion of the Simulation

Ask the student to describe in general what happens when the initial velocity is increased or decreased. Have the students run a model with a much larger timestep. Is the model still stable? Have the students discuss why a model with a larger timestep might not be as good of an approximation, if the model assumes that the force of gravity stays the same throughout a timestep.

Discussion of Observation

Ask the students if they can come up with a way to test if their result is correct. One thing they may come up with is to compare the circumference of the Earth's orbit (2 pi AU) with the Earth's revolution period (365.25days). Does this result agree with theirs? Also, what is the sensitivity?If the Earth were moving a little faster, what would happen to the orbit?A little slower? If it was further out? Closer in? Moving at an angle?Assign them to write a clear and accurate report of what they observed. Emphasize that it is important that they know what software was used, and what parameters were set. Be sure to go through the setup procedure again so that they can record this information.

Collaboration

After they have polished their reports, have the other group of students attempt to repeat the experiment as described in the report, verify the findings of the first group, and provide feedback about their methods and conclusions. Encourage both groups to ask questions of each other's procedure and observations. If another group of students is not available, you could split one class into two large groups and require them to communicate only through writing.Extensions

-

Further Experimentation

Have the students try to see if the mass of the Earth changes the solution. Does it require a large change or a small change? Does it matter if you make the Earth larger or smaller? Does changing the mass of the Sun make a difference? -

Thinking Harder

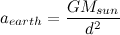

If the students solve for the acceleration of the Earth, they will find it does not depend on the mass of the Earth: Why then does the result of the above simulation change if

the mass of the Earth is made to be comparable to the size of the Sun?

Why then does the result of the above simulation change if

the mass of the Earth is made to be comparable to the size of the Sun?

[ Home | GalaxSee Home | Index ]

[ Introduction | Simulation Software | GalaxSee Help ]

[ Fractal Modeling

Tools | Baroreceptor Modeling | SimSurface ]

[ Gnuplot | The Pit and the

Pendulum | Environmental Models | InteGreat ]

© Copyright 1996 The Shodor Education Foundation, Inc.